On Intelligence

The U.S. Intelligence Community's secret weapon is not secrets. It's context.

I have spent the vast majority of my career in intelligence, not policy. I joined the Central Intelligence Agency when I was 23 years old, and worked my way up the ranks until I became the National Intelligence Officer for Africa under Presidents Obama and Trump. I have published articles on U.S. intelligence analysis on Africa in academic journals, and I teach a course on the topic at The George Washington University. What I’ve learned is that the intelligence community’s secret weapon is not secrets.

In the Eye of the Beholder

It is quite understandable to equate the intelligence community with secrets. It is how the CIA, for example, is portrayed in movies and books. It is central to the institution’s own myth-making and part of its raison d'être. However, in my experience, it is misleading and distracts analysts and policymakers from the true value of intelligence: context.

Don’t just take my word for it. Ray Cline, who led the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence from 1962 to 1966 and served as Director of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the Department of State from 1969 to 1973, complained bitterly that Secretary of State William Rogers didn’t consider information to be "intelligence" unless it had been obtained covertly. Cline insisted that what was important was our “best analysis of what's going on in the world,” four-fifths of which was provided by Embassy reporting or from news services.

Three decades later, CIA senior manager Martin Petersen made the same point, reminding analysts that their ability to situate global developments within a larger cultural and historical context is their most important contribution. After all, he conceded, policymakers “consume vast amounts of raw intelligence—the same stuff intelligence analysts are reading.” In other words, secrets aren’t enough.

When I was Special Assistant to President Biden and Senior Director for African Affairs at the National Security Council, I wanted more analysis and fewer secrets. I knew I was a difficult customer who was quick to debate, question, and challenge what I received from the intelligence community. I had my own opinions based on my studies, experiences, and interactions with African counterparts. But I genuinely believed that if policymakers were going to make the best decision possible, we needed the intelligence community to add context, depth, and breadth to our policy discussions.

Context Matters

Good intelligence analysis is explanatory. It helps one make sense of complex situations — whether it is geopolitical competition, political parties, or particular individuals. It’s what we call analytical tradecraft. And context is essential, especially when the policy debate becomes too heated and overwrought.

For example, in 1962, the intelligence community published a National Intelligence Estimate entitled “Trends in Soviet Policy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa.” It served as a much-needed corrective for the growing hysteria about Soviet expansion in the region. While analysts acknowledged that the Soviet Union saw Africa as “an area of great potential opportunity for the Bloc and international communist movement,” they also highlighted several obstacles to Soviet influence:

The Soviets lack several important assets. They have not had the West’s long experience in tropical Africa. They are handicapped by a shortage of trained and experienced personnel able to move with assurance in the complex world of African politics. Even the question of anti-colonialism, which has provided an entry point for the Bloc, also sets boundaries on the degree of influence that Africans are willing to grant the USSR. To a great extent Bloc gains in Africa have come on the initiative of African regimes which wish to redress the imbalance created by Western influence, but these same regimes have also shown concern to limit the Bloc presence.

This record of nuanced analysis also extended to political organizations. In an African Affairs article in 2003, Jeffrey Herbst commended the intelligence community’s balanced assessments on apartheid South Africa. While U.S. foreign policy specialists had frequently adopted a narrow ideological view, intelligence analysts rejected cartoonish and inaccurate characterizations, especially of the African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Communist Party (SACP). In 1986, the CIA assessed:

The ANC. . .is not a monolith nor do we believe it is under the firm control of any one cohesive group. In our judgment, the SACP (in part because of its long history of support for the ANC and its dedicated and ideologically committed leadership) has a considerable degree of influence in the ANC — particularly ANC’s military wing. At the same time, however, we believe that generational, racial, and ideological differences within the ANC act as a brake against any SACP attempt to gain domination over the total control of the ANC.

And there are countless examples of deeply drawn portraits of African leaders. As I wrote earlier this year in Studies in Intelligence, a leadership profile, when done well, is a “revealing and yet remarkably succinct study of a leader’s hopes and dreams, attitudes and demeanor, and friends and enemies at home and abroad.”

In 1961, the intelligence community judged that Sudanese leader General Ibrahim Abboud appeared to be “a sincere patriot, disgusted by the corruption among the civilian politicians, convinced that nonparty government is best for his country, and aware that the army is one of the few instruments capable of bringing about a change.”

In 1970, the CIA assessed that Malawian President Hastings Kamazu Banda was a “politician of consummate skills” who had a “deceptively mild appearance that masks an explosive temper and demagogic, overbearing manner. He enjoys enormous prestige within his country as the man who took the former British dependency of Nyasaland out of the unpopular Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland and to independence as Malawi.”

And, in 1984, analysts concluded that Burkinabe leader Thomas Sankara’s revolutionary rhetoric “so far has not been translated into drastic social or economic restructuring at home. This cautious approach most likely reflects Sankara’s need to avoid alienating France, other members of the European Community, and the World Bank—Burkina’s major aid donors.”

Depth of Expertise

When I started my career at the CIA, I was taught the virtues of concision and precision. It was a sign of one’s technical skills to be able to convey complex concepts in as few words and sentences as possible. The theory behind this approach is straightforward: policymakers are very busy and don’t have the time to wade through pages and pages of analysis. At the White House, I generally found this to be true. Usually, I just needed the bottomline judgment to inform our policy process. At other times, though, I needed more. I wanted stronger argumentation and more fulsome examples to help me think through an urgent crisis or an emerging opportunity.

The intelligence community, in my opinion, was sacrificing persuasiveness in the name of brevity. And it doesn’t have to be this way. There is an extraordinary record of deeply researched intelligence assessments. Here are just a handful of titles from the CIA’s FOIA reading room:

Ghana's Political and Economic Malaise (July 1967)

Ethiopia Dynamics of Succession (December 1968)

Power Politics Drift Into the Western Indian Ocean (April 1969)

Rural-Urban Migration in Black Africa (December 1970)

Implications of Madagascar's Unfinished Revolution (February 1972)

Nigeria: Small Return on Oil Wealth (September 1978)

Rice Shortages in West Africa: Potential for Political Instability (July 1982)

Cuban Presence in Sub-Saharan Africa (August 1986)

Southern Africa's Beira Corridor: A Vulnerable Route (January 1987)

African Group Voting Behavior in the UNGA (December 1988)

To be sure, it requires experience to know what needs elaboration and what doesn’t. I found longer analytical pieces to be enriching, deepening my understanding and serving as a perfect pairing for briefings, discussion papers, and talking points for NSC leadership. Moreover, I knew from my own career that just writing these papers would sharpen future analysis. I couldn’t agree more with Adam Grant who recently posted that “writing is where we do our best thinking.”

During my first couple years as a junior analyst, I would write what we called “bookshelf” pieces — breaking down a country’s top challenges into three or four separate assessments. I was not always certain that a policymaker would read my tomes on niche political topics, but they prepared me to respond effectively to crises and have thoughtful answers at the ready when asked hard questions. By writing longer, in-depth pieces, analysts inevitably become more sophisticated in their thinking and their contributions become more relevant to the policy process.

Breadth of Coverage

Perhaps one of the biggest mistakes consistently made by intelligence leaders is to disproportionately cover the crisis du jour at the expense of the smaller, often under-the-radar issues. Don’t get me wrong: when I was at the NSC, I appreciated analysis on the major conflicts or important elections. Those assessments were part of my daily digest and served as one of many inputs I relied on to navigate a priority topic. But they were rarely decisive and often did not significantly advance my understanding of a topic. After all, I was spending most of my time on those urgent challenges, and I had the benefit of additional insights from my conversations with foreign counterparts and non-government experts, as well as e-mails from the interagency that analysts may not have seen.

What I wanted and needed was coverage of the rest of the continent. What were the latest political developments in smaller countries? What was the state of military readiness across the region? How were economic reforms progressing in specific regions? What was the outlook for relations between African countries and their partners in Latin America, the Middle East, South Asia, or East Asia? Since I was less likely to receive such updates elsewhere, these kinds of intelligence assessments had the potential to point up both emerging problems and exciting opportunities. At the minimum, they ensured we were informed about what was happening across a vast and diverse continent.

That’s what the intelligence community did in the past and should continue to do. Intelligence analysts have written on every country and every issue, even when policymakers explicitly lowered Africa as a national security priority.

The Johnson Administration decided to phase out bilateral assistance for some twenty-five countries in Africa. And yet, the CIA wrote at least 29 intelligence assessments on Benin, 28 on Burundi, 26 on Sierra Leone, 15 on Zambia, 14 on Uganda, and 12 on Congo-Brazzaville between November 1963 to January 1969.

At the beginning of President Nixon’s first term, Africa was consigned to a low priority and Henry Kissinger, later as Secretary of State, famously disdained the Department’s Bureau of African Affairs. However, according to declassified records, the CIA published some 1,000 products on Africa from 1969-1976.

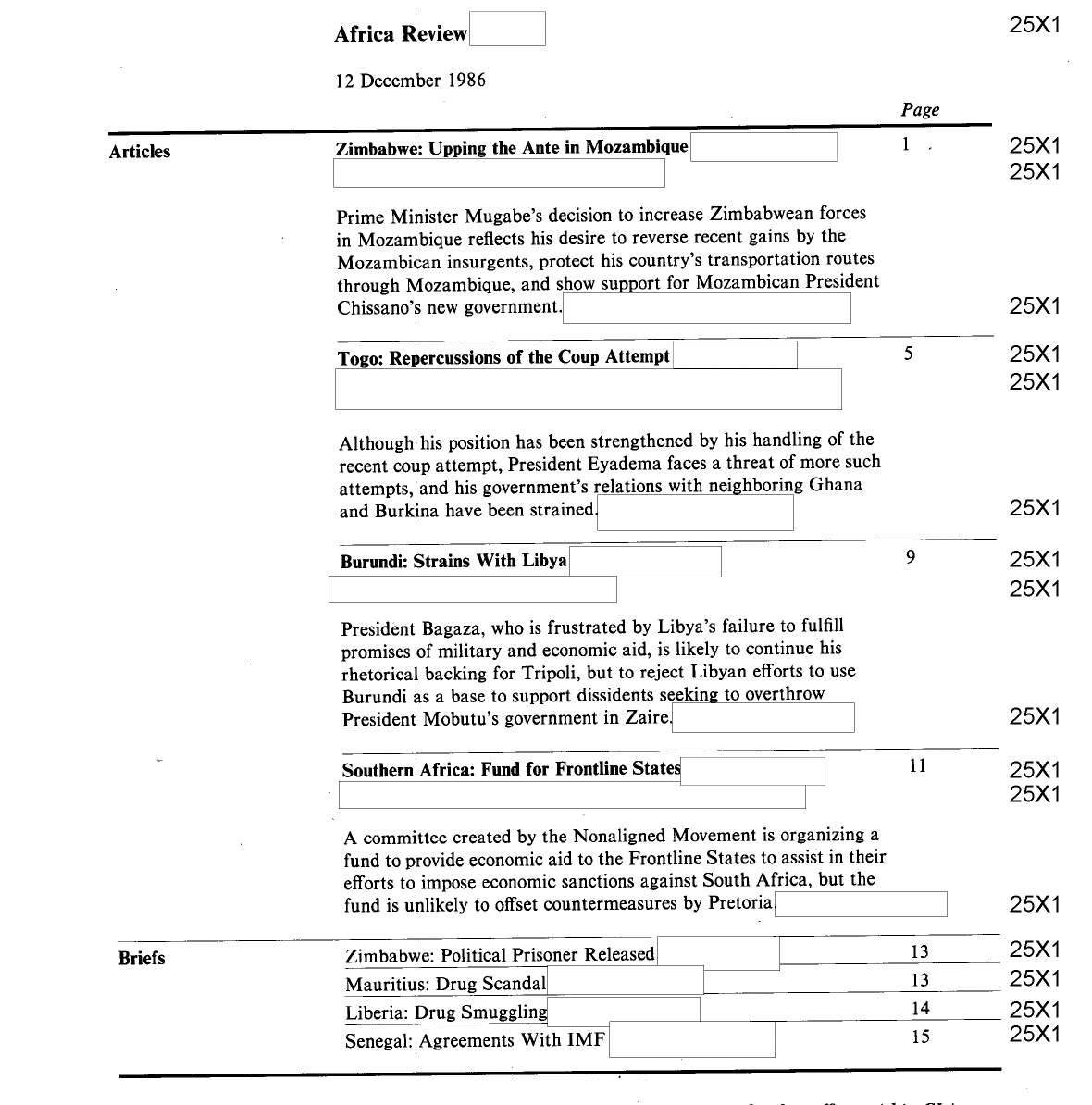

As early as August 1978, the CIA started to produce the “Africa Review.” It was an essential publication for analysts to cover the full breadth of developments across the region that otherwise wouldn’t have made threshold for President’s Daily Brief or other analytic products. From a special issue on insurgencies in Sub-Saharan Africa to analysis on Nigeria’s 1988 budget and a profile of the Comoran opposition in 1985, there was rarely a subject they missed.

Just Do It

This is all very possible to do. Even with a small cohort of analysts, there is an opportunity to produce assessments that provide context, as well as showcase the depth and breadth of expertise. Indeed, in November 1984, Deputy Director of Intelligence Bob Gates sent a memo to Director of Central Intelligence Bill Casey stating that while only about 30 CIA analysts worked on sub-Saharan Africa, they consistently punched above their weight. Gates went on to list their astonishing record of production from the prior year:

In addition to contributing about seven percent of the information for the DI’s daily current intelligence publications, analysts covering African issues:

delivered over 450 briefings to members of the Executive Branch and Congressional committees

produced some 200 specially tailored typescript memoranda, analytical assessments, and longer research papers, plus about 600 biographic reports.

Post Strategy

I am convinced that it is more important than ever to write about the continent. We need insights on major developments, as well as seemingly minor ones that have the potential to affect U.S. interests. It would certainly be a mistake to diminish the intelligence community’s coverage of Africa under the guise of “efficiency” and cost-cutting measures. Analysts have to write -- non-stop. That’s how they deepen their expertise, sharpen their critical thinking, and feed their curiosity. And it’s how we avoid strategic surprise, seize opportunities, and advance U.S. priorities in Africa. The good news is we don’t need secrets to do this, just context.