On the Oval Office

We ranked 12 U.S. Presidents on their Africa policies. The results are surprising.

In my very small (and very nerdy) social circle in Washington, D.C., we occasionally debate which U.S. president had the most consequential policy toward Africa. Partisans usually point to dollars spent, programs announced, or conflicts resolved to make their case on behalf of one administration or another. But, if you really want to judge a president’s record, all you have to do is look at the number of Oval Office meetings with African leaders.

Why Oval Office meetings?

It may seem obvious to point to the Oval Office. After all, it is the seat and symbol of U.S. power. My research of U.S. policy toward Africa since the late 1950s, however, indicates that it is the most reliable predictor of a robust U.S. policy toward the region.

It’s all in the numbers: presidents who meet with more African leaders, on balance, launch more initiatives, introduce more policies, and engage more Africans on global issues. Everything flows from the Oval Office.

Ranking U.S. Presidents

To test this theory, we decided to crunch the numbers. With help from Bobby Pittman, who served as President Bush’s Senior Director for African Affairs at the National Security Council from 2006 to 2009, I went through every U.S. presidential meeting with African and non-African leaders at the White House from January 1961 to January 2025.

A few methodological notes: (1) we used the Department of State’s Office of the Historian website to track all African and non-African meetings; (2) we only included meetings if they were substantive, and separate from a larger event — attending the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in 2014 or 2022, for example, wasn’t enough to make the cut; (3) we counted meetings with three, four, or six leaders as separate entries; (4) we excluded North African countries consistent with the U.S. government’s bureaucratic divisions, and (5) we omitted phone calls, foreign trips, and meetings in New York during the UN General Assembly.

It shouldn’t come as a shock that President George W. Bush topped the chart. Bush spent more time with African leaders than any other U.S. president. By our count, he spent 3 percent of his working days in meetings with African leaders, which roughly translates to hosting an African counterpart every 33 days.

As a result, Bush prioritized Africa in his signature initiatives, including the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). By the time Bush announced PEPFAR in his State of the Union speech in January 2003, he had already hosted 14 African leaders at the White House — more than Trump and Biden combined — and discussed the devastation caused by HIV/AIDS with many of them. In his speech, he asked Congress to “commit $15 billion over the next five years, including nearly $10 billion in new money, to turn the tide against AIDS in the most afflicted nations of Africa and the Caribbean.”

His record number of engagements tracks with his exemplary legacy. In addition to PEPFAR, the President's Malaria Initiative, and the Millennium Challenge Corporation, Bush helped to resolve conflicts in Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Sudan. Under his watch, the U.S. Department of Defense established the U.S. Africa Command in 2007, which is responsible for U.S. military activities on the continent (excluding Egypt).

In a 2017 interview, Bush stressed the importance of his engagement: “if an African leader has worked with and befriended a U.S. president, it makes discussions a lot easier. It’s just a matter of personal diplomacy. I spent a lot of time with African leaders and had very good relationships with them.”

Kennedy’s extraordinary level of engagement is also unsurprising. Not only did he spend 2.6 percent of his total working days with Africans, he met with more African counterparts as a percentage of his foreign leader engagements than any other U.S. president. According to our research, Kennedy’s Africa meetings represented one-fourth of all foreign leader encounters during his administration.

Kennedy elevated Africa as a U.S. policy priority. As early as 1959, he declared that “the future of Africa will seriously affect, for better or worse, the future of the United States.” Kennedy’s consistent focus on the continent made it an imperative for the rest of the U.S. government. Within a month of taking office, Kennedy met with the National Security Council to revise U.S. policy toward the region. His first nominee for the Department of State was not the secretary of state, but the assistant secretary of state for African affairs — a former governor of Michigan. He named prominent political party operatives as ambassadors to Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Senegal, and Sierra Leone.

One White House staffer even complained about Kennedy’s affection toward Africa, asking “how many votes are there in Mauritania” in a pique of anger after JFK’s two-hour-long meeting with Mauritanian President Moktar Ould Daddah in November 1963.

Kennedy’s commitment to personal engagement with Africans translated into major U.S. policy outcomes, including the establishment of the Peace Corp and U.S. Agency for International Development. And, at least in part due to his personal ties, he persuaded the Guineans, Ghanaians, and Senegalese to deny landing rights to Havana-bound Soviet aircraft during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Presidents Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush also scored high in the rankings, and both of them were committed to integrating Africa into global conversations. Their engagement ensured that the region was treated as an essential, not extraneous, part of U.S. foreign policy.

One year into his presidency, Carter told the Democratic National Committee that “for too long our country ignored Africa.” Carter made the first U.S. state visit to the region, and he was deeply involved in crises in Rhodesia and the Horn of Africa. Carter never missed an opportunity to discuss world affairs with visiting Africans. He raised nuclear nonproliferation and Middle East peace with Nigerian leader Olusegun Obasanjo; opined on Iran and Afghanistan with Senegalese President Leopold Senghor; and touched on developments in Iraq with Kenyan President Daniel arap Moi.

Bush, similarly, had deep experience on Africa, following stints as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and CIA director. As vice president, he traveled to Cape Verde, Senegal, Nigeria, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Kenya, and Zaire. Accordingly, he sought out African counterparts’ opinions on international developments. He shared the results of a NATO summit with Botswana’s President Quett Masire; talked about Yemen with Mozambican President Joaquim Chissano; and discussed a terrorist attack in Trinidad and Tobago with Togolese President Gnassingbe Eyadema.

Big Surprises

What is striking about our results is how it changes our understanding of which presidents were more involved in Africa. Contrary to conventional wisdom, every Cold War-era president spent more time with African counterparts than their post-Cold War successors, save for George W. Bush. Our data flips the whole historical narrative of neglect during the Cold War and attention in the post-9/11 era.

President Lyndon Johnson, for example, has long been dismissed as being disinterested and disengaged on Africa. And yet, Johnson spent 16 percent of all foreign engagements with African counterparts. LBJ travelled to Senegal as Kennedy’s vice president and dispatched Vice President Hubert Humphrey on a two-week trip to the region. He personally engaged on the Nigerian Civil War and various Congolese crises, going so far as to ask his staff to develop a “Johnson Doctrine” for Africa. U.S. diplomats, in response, advised the White House that “for policy objectives to be advanced, it is desirable that African leaders be made aware of the US President’s personal interest in African affairs.”

Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford have also been tagged as missing in action on the continent. Indeed, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger initially asked his CIA briefer why there were so many Africa articles in the President’s Daily Brief, explaining “our attention, the attention of Mr. Nixon and myself, is going to be centered on the Soviet Union and Western Europe.” Nixon and Ford, however, performed better than expected. In 1957, Nixon recommended the establishment of the Africa Bureau at the Department of State, and welcomed President Emile Zinsou of Dahomey (now Benin) as his first foreign visitor to the White House in March 1969. Ford, who met with eight leaders during his short tenure, directed Kissinger to pay more attention to southern Africa after Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda delivered a fiery critique of U.S. policy during his visit to Washington in August 1975.

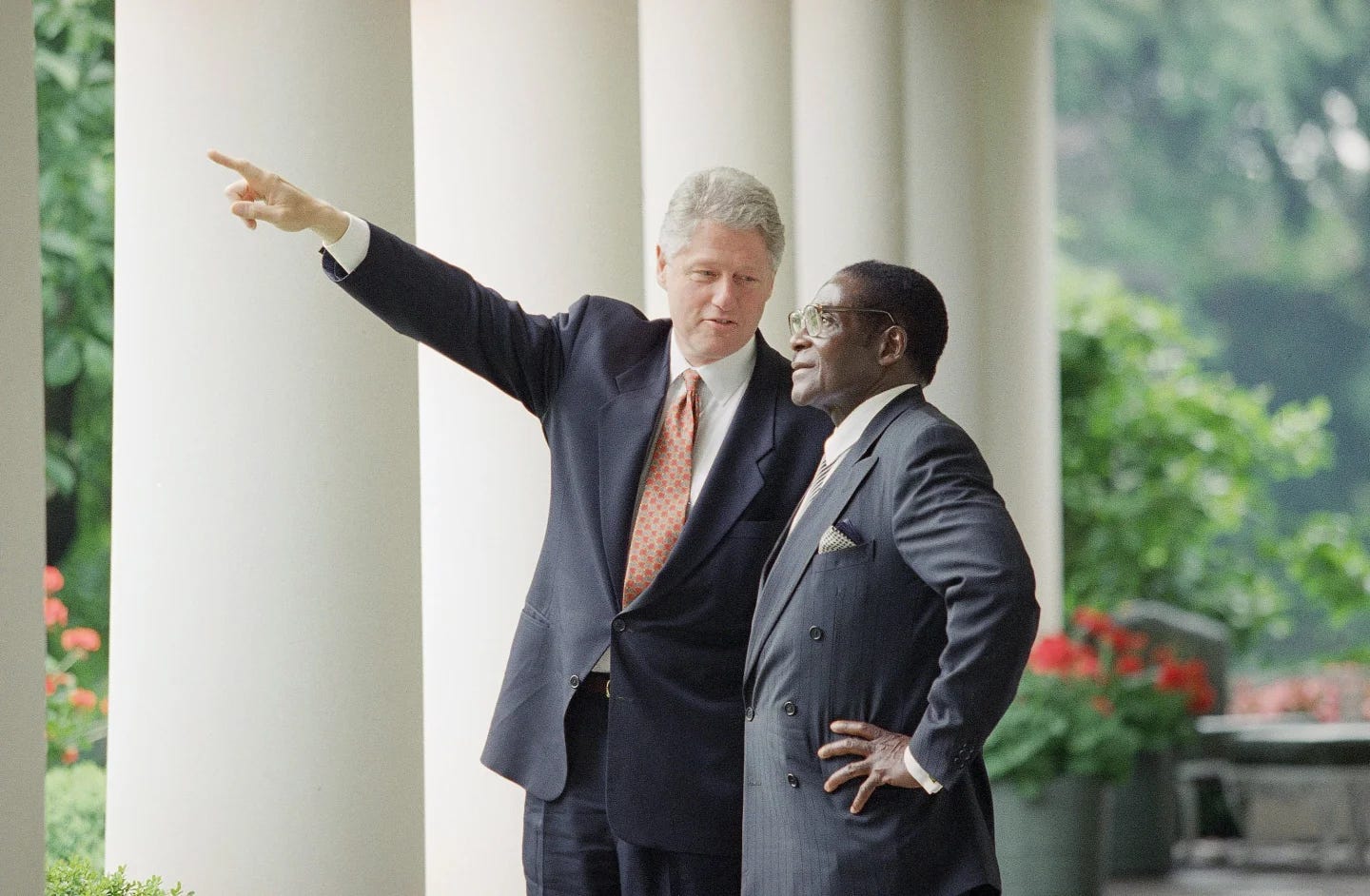

Presidents Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Donald Trump, on the other hand, spent far less time with African leaders. Trump had the lowest score of all U.S. presidents; he hosted Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta twice and met Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari once. The three most recent Democratic presidents also performed poorly relative to their predecessors — dedicating only about 1 percent of their total working days to African meetings.

Clinton’s relatively limited time with Africans —only 5 percent of his total foreign leader engagements—tracks with an administration that stripped away resources and reassigned personnel from Africa in 1993. As I detailed in a Foreign Affairs article last year, Clinton approved the development of a new approach only after reading Robert Kaplan’s “The Coming Anarchy” in early 1994. Even with two trips to the region and signing the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) into law, his administration struggled to stay focused due to domestic and foreign distractions. Clinton’s engagement varied wildly year to year: he hosted two African leaders in 1993, four in 1994, five in 1995, zero in 1996, one in 1997, three in 1998, three in 1999, and one in 2000.

Big Setbacks

If more presidential engagement often leads to new initiatives and important foreign policy outcomes, what is the cost of less presidential involvement? My own experience as National Security Council Senior Director for African Affairs during the Biden Administration is telling.

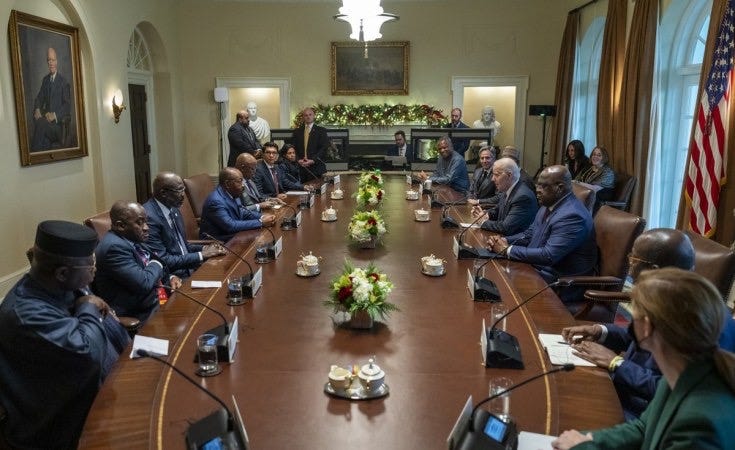

President Biden hosted ten African leaders at the White House, representing about 10 percent of all his total foreign meetings and 1 percent of total work days. I suspect that’s better than most people would have assumed, though it’s in large part because he simply had fewer foreign leader gatherings than most of his predecessors and because he met with six presidents during one meeting on the margins of the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit.

Upon reflection, I ended up having to make some painful choices because it was evident that we would only have a few chances to invite African leaders to the White House. I spent my political capital on the heavyweights, namely Kenya, South Africa, Nigeria, and Angola. I opted for meetings that were safe because I had little room for error. I shied away from opportunities to schedule a quick encounter with a visiting head of state because I feared I would forfeit one of my slots. I even looked askance at suggestions to arrange a repeat meeting because it meant fewer leaders would have had a chance to enter the Oval Office.

My takeaway is that when presidents don’t regularly meet with African counterparts, they don’t develop close ties, don’t press for big initiatives, and don’t view Africa’s contributions to global challenges as vital. And, most problematically, Africa becomes more of a box-checking exercise than part of a strategic endeavor.

Post Strategy

I am convinced that presidential engagement is the indispensable factor in an effective U.S.-Africa policy. It can’t be outsourced to the vice-president, secretary of state, or other cabinet members. It certainly can’t be left to assistant secretaries and senior directors. Unless a president engages — frequently and with a diverse group of the region’s leaders — it is near impossible to significantly and profoundly advance U.S. interests. If you don’t believe me, just look at the data.

There is a desperate need for more non-partisan data-driven analyses like this one!

Fantastic piece! I can’t tell you how many raised eyebrows I’ve gotten over the years when I’ve told people that Pres George W. Bush did more for Africa than most other U.S. presidents and that he was such a great customer to write for as a CIA Africa analyst due to his engagement with the material. It’s nice to see the data to back that up! Well done!