On UN Speeches

Are U.S. presidential speeches at the UN General Assembly important to U.S.-Africa policy? It depends.

I thought I was being clever. With the help of several large language models, I had planned to analyze every reference to Africa in every U.S. presidential speech to the UN General Assembly since 1960. Like my post on oval office meetings, I wanted to produce a new ranking of U.S. presidents based on how much they discussed Africa at the UN. My hope was that it would reveal something essential about U.S.-Africa relations.

It was an utter failure. It turns out that there is little correlation between a president’s words at the UN and his deeds on the continent. It left me with the distinct impression that UN speeches aren’t particularly useful barometers of presidential interest, especially in Africa. And, if that’s true, what is their utility and function in foreign affairs? Most importantly, how much time (and political capital) we should expend to fight over words?

The Eisenhower Example

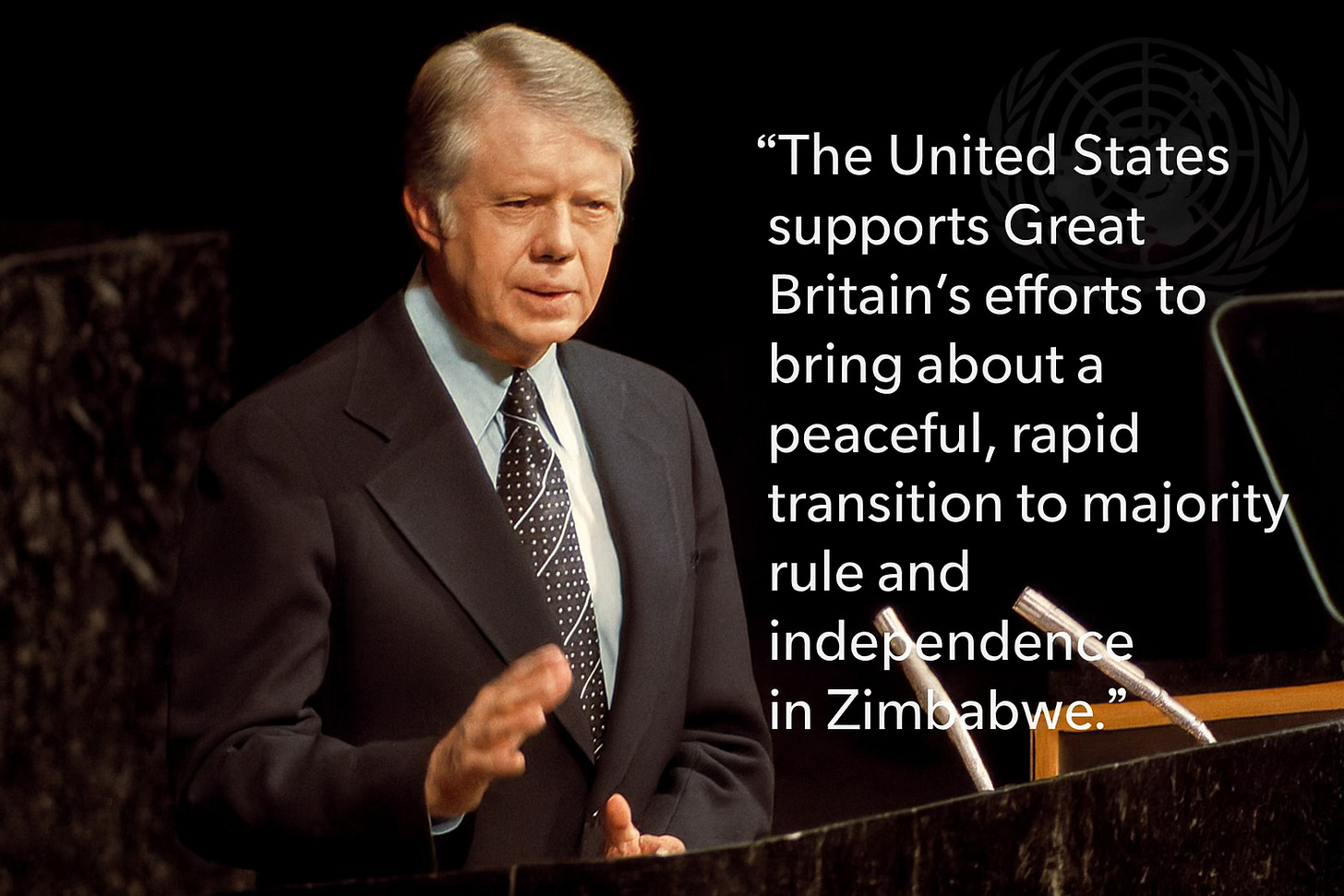

In September 1960, President Dwight Eisenhower started his speech at the UN General Assembly with a warm welcome to its new African members. He remarked that “the people of the United States join me in saluting those countries which, at this session of the General Assembly, are represented here for the first time.” He talked about a region “rich in human and natural resources and bright with human promise.” He also specifically addressed the UN effort in the Congo, warning against interference by other nations and pressing his counterparts to pledge substantial resources to meet the country’s emergency needs.

Eisenhower’s speech, in many ways, was a high-water mark for U.S. presidential speeches at the UN General Assembly. Despite not having a particularly impressive record on Africa, Eisenhower used his time at the podium to advance U.S. policy toward the region. Remarkably, he talked about Africa more than any other U.S. president at the UN; Eisenhower dedicated about fifteen percent of his speech to Africa whereas his successors mentioned Africa or African countries only a few times — about 1 to 5 percent on average. (Note: I used ChatGPT and Claude for the calculations. The results were frustratingly inconsistent, and I suspect not entirely accurate, but Eisenhower was always at the top of the rankings by a large margin.)

Wasteful Moments

In reviewing every speech by every U.S. president at the UN General Assembly from 1960 to 2024, I was struck by how the number of Africa references often had no bearing on how much or how little time and resources a president devoted to Africa policy. For example, President John F. Kennedy—who met with an African leader, on average, once a month during his 1,000 days in office—dedicated only a short paragraph about Congo in his 1963 address. He was even more brief in 1961, commending the UN for its contributions “in the Middle East, in Asia, in Africa this year in the Congo—a means of holding man's violence within bounds.”

In general, most U.S. speeches referenced Africa to support a larger policy point or because it had some rhetorical resonance. While I am a firm believer of not treating Africa as a region apart, many of these brief mentions seem like throw-aways and missed opportunities. By treating African triumphs and tribulations as oratory flourishes, we papered over the substance and squandered a chance to advance our policy goals.

Global Examples. In almost every U.S. speech, an African conflict is lumped together with other global conflicts to substantiate a bigger message. In his 1992 address, President George H.W. Bush decried that “as we see daily in Bosnia and Somalia and Cambodia, everywhere conflicts claim innocent lives.”

Rhetorical Devices. U.S. presidents often avail themselves of Africa’s alliterative possibilities, stringing together ideas into powerful soundbites. In 2011, President Barack Obama intoned that “we saw in those protesters the moral force of non-violence that has lit the world from Delhi to Warsaw, from Selma to South Africa —and we knew that change had come to Egypt and to the Arab world.”

Box-Checking Exercises. To cover as many topics as possible, U.S. presidents will pepper their speeches with brief references to specific African issues. In his 1993 speech to the General Assembly Hall, President Bill Clinton name-dropped Angola, Eritrea, Namibia, Somalia, and South Africa.

Purposeful Moments

Some U.S. presidents, however, used the UN’s bully pulpit to great effect. Instead of delivering one-liners about Africa, they seized the moment to address a pressing topic or concern. In these cases, U.S. speeches at the UN were a call-to-arms, an attempt to rally world opinion around a U.S. program or policy toward the region. The emphasis was on future opportunities, not past events.

Demanding UN Action. A few U.S. presidents used their time at the podium to propose new UN initiatives or reiterate their support to implement specific UN resolutions. In 1960, Eisenhower expounded on his vision for “an-all out United Nations effort to help African countries launch such educational activities as they may wish to undertake.” He enumerated five principles and programs that should undergird UN efforts toward the region.

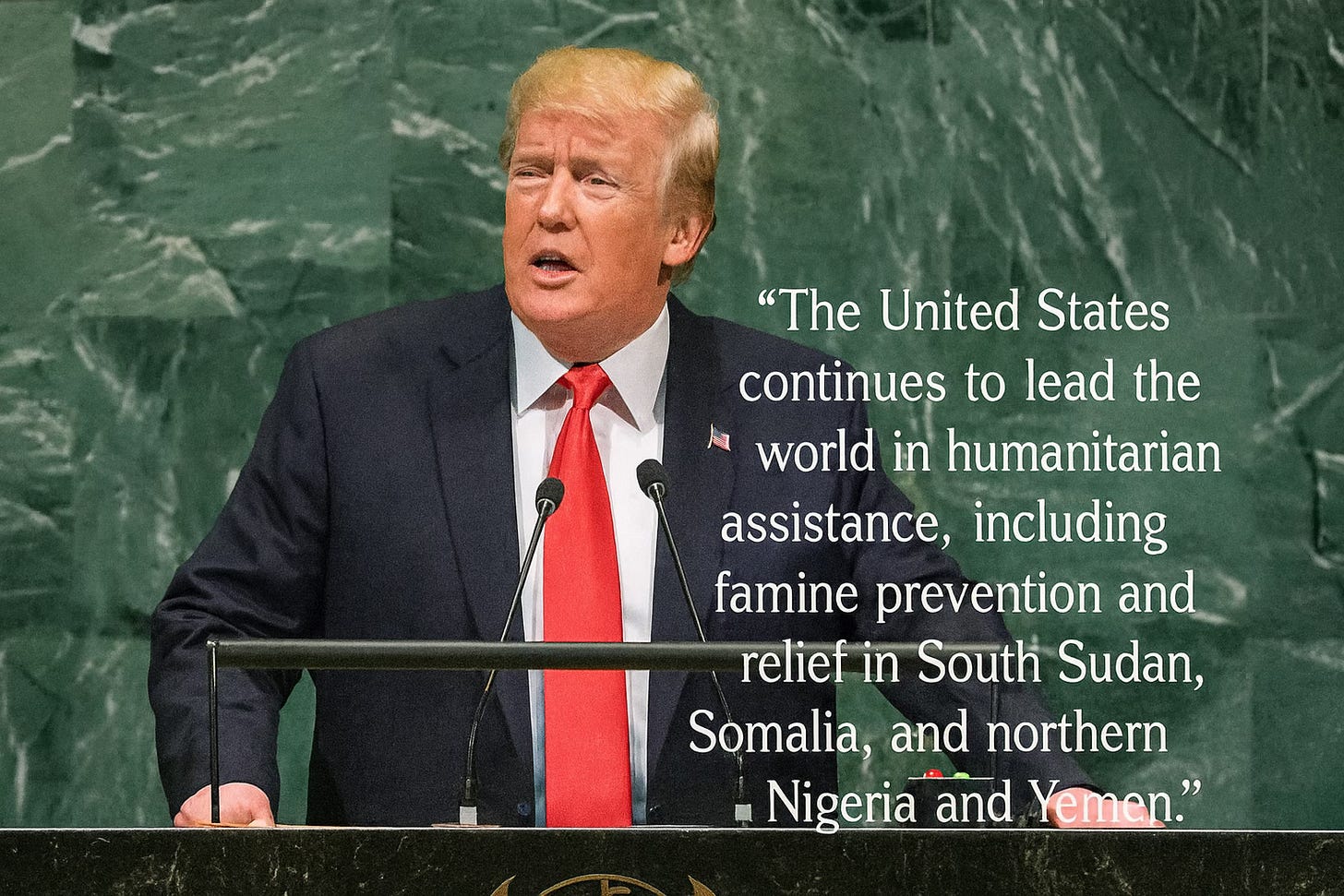

Showcasing U.S. Programs. U.S. speeches at the UN occasionally served as platforms to promote U.S. programs. In 2005, President George W. Bush talked about his commitment to address the scourge of infectious diseases, sharing that the United States is “ahead of schedule to meet an important objective, providing HIV/AIDS treatment for nearly 2 million adults and children in Africa” and has “set a goal of cutting the malaria death rate in half in at least 15 highly endemic African countries.”

Explaining U.S. Policies. Some U.S. presidents directly engaged their foreign and domestic audiences on U.S. positions regarding the Cold War or apartheid South Africa. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan stressed “how difficult it is for the United States to accept Soviet assurances of peaceful intent when …1,700 Soviet advisers and 2,500 Cuban combat troops are involved in military planning and operations in Ethiopia; when 1,300 Soviet military advisers and 36,000 Cuban troops direct and participate in combat operations to prop up an unpopular, repressive regime in Angola.”

The Biden Experience

I admit that when I served as President Biden’s Senior Director for African Affairs at the National Security Council, I usually kept my powder dry on UN speeches. To be sure, I wanted Africa mentions, but I wasn’t sure how much room I had to press for new language and whether it was worth the political cost.

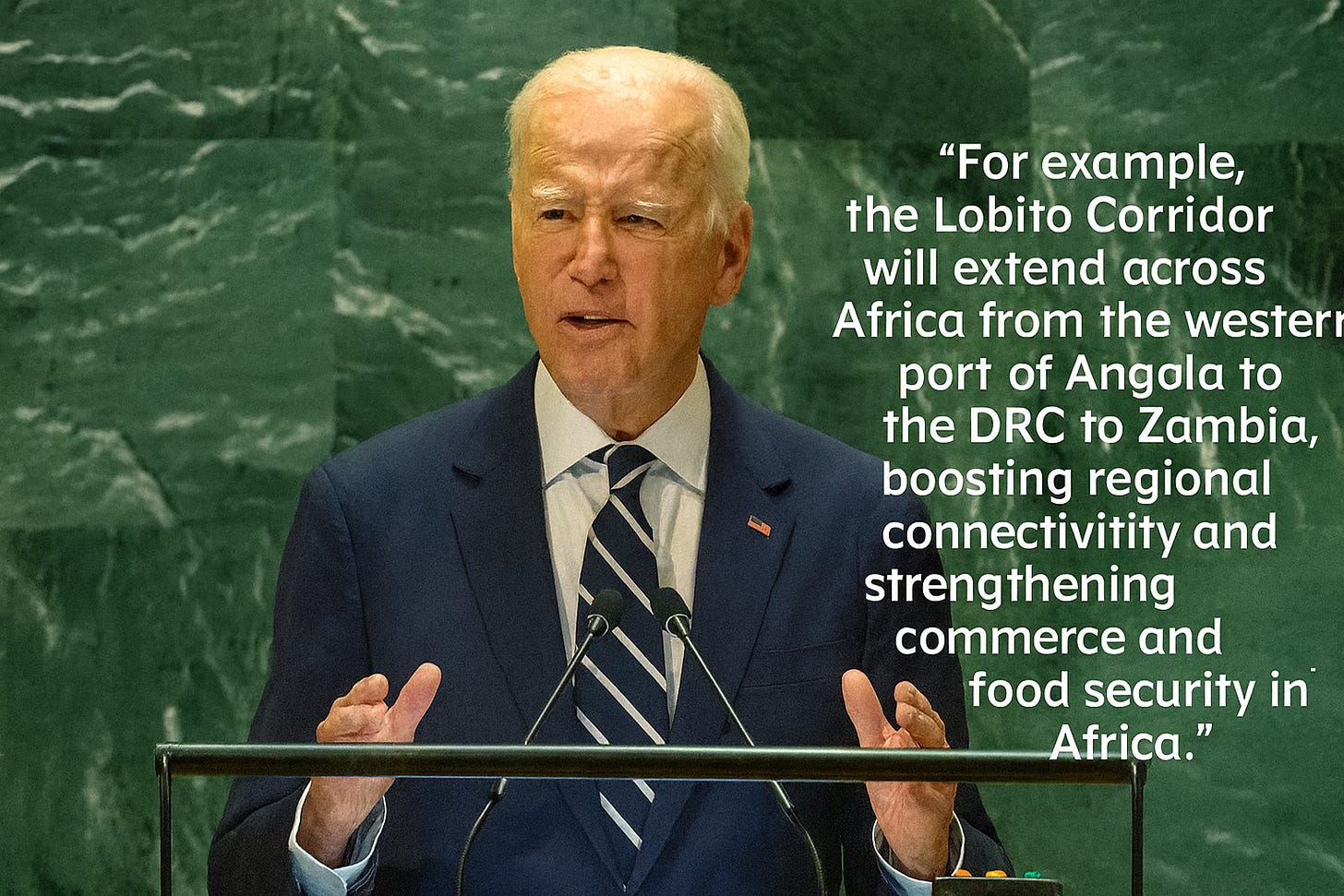

The truth is that the 2022 and 2023 UN speeches came pre-loaded with Africa references, including nods to the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit and the African Union’s admission as a permanent member of the G20. There were brief mentions on the conflict in Ethiopia, and a few paragraphs on restoring constitutional rule in West Africa. My Western Hemisphere counterpart inserted language about the Kenyan police mission to Haiti. And, of course, there was a nice chunk about the Lobito Corridor. Rightly or wrongly, I focused more on ensuring the speech’s accuracy than generating new content.

The Next Fight Over Words

Is there a better approach? It depends on what one deems important. Within the U.S. policy process, you gain significant leverage within your own bureaucracy or the interagency if the president publicly comments on specific policies or programs related to your region. Save for new resources, it is the best way to demonstrate to your colleagues that what you are pushing is a presidential priority. Within the international community, there also are advantages to singling out certain hotspots or issues. The world takes notice; in Ben Rhodes’s book, The World As It Is, he recounts how Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan recited parts of President Obama’s UN speech back to Obama.

A UN speech is different than the State of Union (which I plan to tackle in a post at some point) or a foreign policy speech on an official trip. It is one of the few venues where a president talks almost exclusively about world affairs without having to hold (too much) space for domestic politics. The U.S. president can deliver a global message, distilling his foreign policy philosophy into a few thousand words. This is especially relevant for Global South countries whose leaders tend to receive fewer invitations to the Oval Office. It is a rare and powerful opportunity to speak directly to them.

But just because it is a foreign policy speech, we shouldn’t try to jam it with as many Africa mentions as possible. The goal is to advance policy, not tally up word counts. Indeed, U.S. presidents used to routinely skip the speech in the 1960s and 1970s; President Lyndon Johnson never went to the General Assembly’s annual September session during his time in office. It underscores the point that what is most important is what a president does, not what he says. In the next fight over UN speeches, we should prioritize quality over quantity.

Post Strategy

There’s a reason why my attempt to rank U.S. speeches at the UN was such a failure (besides the AI glitches). When U.S. presidents talk about Africa, it is too often in phrases, not paragraphs. There may be more volume, but that’s not an indicator of substance. And it certainly doesn’t lend itself as a proxy for presidential record.

I am convinced that UN speeches have an important role in policy stagecraft, but it is easily overstated. It might be ok to say less about Africa—as long as the words the president does say truly matter.

Great read. How do you think future administrations should balance rhetorical recognition of Africa with actual policy commitments?